The Darwin and Gender blog now has a new home at the Darwin Correspondence Project website — please change your bookmark to keep up with our latest posts!

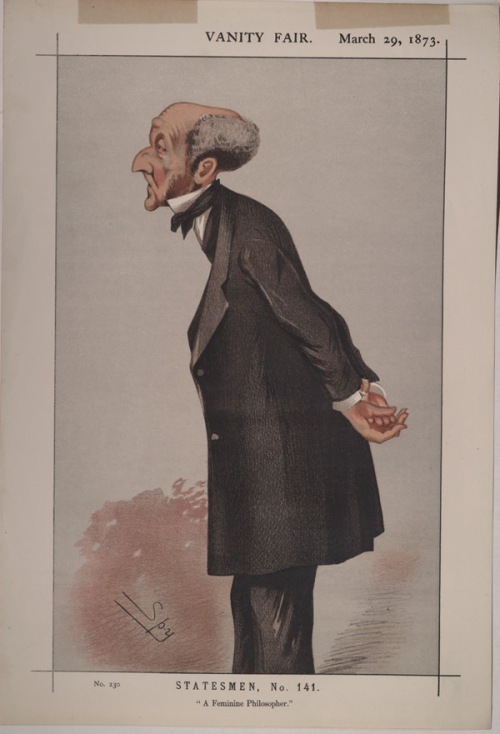

Charles Darwin is not well known as a promoter of women’s rights. Indeed, much of his work explicitly opposed the arguments for sexual equality put forward by first wave feminists of the nineteenth century. In The Descent of Man, for example, Darwin makes explicit reference to Harriet and John Stuart Mill’s early feminist work The Subjection of Women (1869) which, he said, ignored the fact that there existed fundamental and enduring “differences in the mental powers of the sexes“.

The differences in the intellectual capacities of men and women, Darwin said, were the inevitable product of the evolutionary process; where men had honed their brainpower and skills of dexterity through combat with rival males, women had evolved primarily off the back of their physical attractiveness and as such were creatures of beauty but not intellect;

“Although men do not now fight for the sake of obtaining wives,” Darwin said, “…yet they generally have to undergo, during manhood, a severe struggle in order to maintain themselves and their families; and this will tend to keep up or even increase their mental powers, and, as a consequence, the present inequality between the sexes”. Thanks to the workings of the evolutionary process, then, women were naturally inclined toward a life of domesticity centered around “the early education of our children” and on ensuring “the happiness of our homes“.

Given his views on women’s intellect and their corresponding social role, Darwin’s correspondence with Lydia Becker comes as something of a surprise. Becker was a leading member of the suffrage movement, perhaps most well known for publishing the Women’s Suffrage Journal between 1870 and 1890. She was also a successful biologist, astronomer and botanist and, between 1863 and 1877, an occasional correspondent of Charles Darwin.

Given his views on women’s intellect and their corresponding social role, Darwin’s correspondence with Lydia Becker comes as something of a surprise. Becker was a leading member of the suffrage movement, perhaps most well known for publishing the Women’s Suffrage Journal between 1870 and 1890. She was also a successful biologist, astronomer and botanist and, between 1863 and 1877, an occasional correspondent of Charles Darwin.

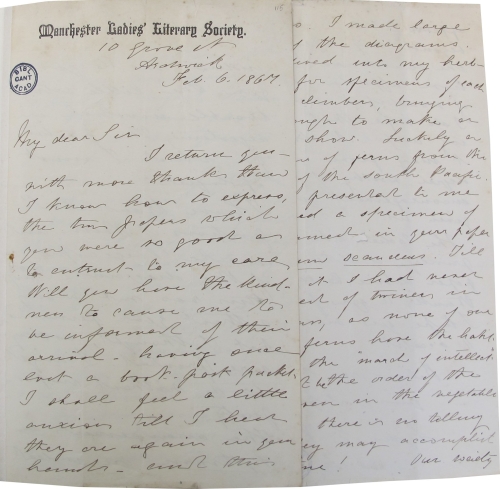

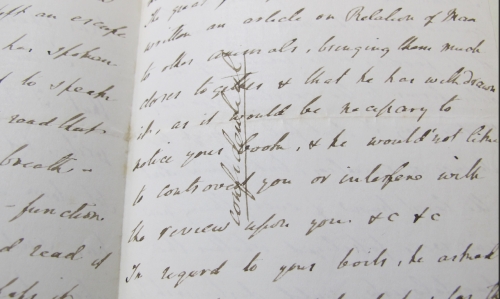

Initiated tentatively by Becker in a detached letter in 1863, the majority of correspondence between Becker and Darwin concerned the suitably a-political topic of botany. Becker provided Darwin with samples from plants indigenous to her home town, Manchester. She also provided detailed observations which helped feed into his ongoing work on plant dimporhism. In return, Darwin acted as something as mentor to Becker; he responded to her questions, gave feedback on her writing and advised on where best to publish her articles.

Letter from Becker to Darwin written on the headed paper of the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage

Perhaps most surprising, though, was Darwin’s willingness to provide Becker with material to be used as part of an education initiative at her local scientific feminist organisation, the surreptitiously titled Manchester Ladies’ Literary Society. Thus, on December 22nd 1866 Becker wrote to Darwin to ask if he would “be so very good as to send us a paper to be read at our first meeting”. “Of course we are not so unreasonable as to desire that you should write anything specially for us” Becker said, “but I think it possible you may have by you a copy of some paper such as that on the Linum which you have communicated to the learned societies but which is unknown and inaccessible to us unless through your kindness.”

Darwin responded by sending not one but three papers to be read at the ladies’ inaugural meeting.[1] Whether Darwin realised that he was providing materials for a feminist organisation is unclear, although Becker’s use of headed paper and the enclosure in her letter to Darwin of the society’s first pamphlet certainly made no secret of her political affiliations.

Regardless, what is interesting is that despite what he said in the public context about women’s intellectual in-capabilities and designated social role, in private his thoughts and actions were very different. Darwin was happy to work in collaboration with many women like Becker. He encouraged women’s scientific interests wherever possible, frequently sharing observations, samples and reading materials with women across the world. In some rare instances he was even happy to acknowledge that a woman’s scientific skill and knowledge might be superior to his own!

Why Darwin’s private actions so dramatically defied his public statements on women is difficult to decipher. Seen in the context of attacks on men like J. S. Mill – whose support for sexual equality rendered him “feminine” to the Victorian mind – it might have been the case that Darwin was anxious to protect his masculinity. This might have been particularly important at a time when science was increasingly deemed to be a pursuit for strong-minded, rational, perhaps even pedantic individuals – all distinctly masculine characteristics.

As we’ve seen elsewhere, it might also have been the case that respectable men of science were required to tow the ‘establishment’ line, irrespective of their personal convictions. Regardless, what Darwin’s correspondence with women like Lydia Becker shows very clearly is that however dominant nineteenth-century gender ideology might appear through analyses of mainstream published material, we need to look more broadly and think critically about the impact of ideology in real terms if we’re ever properly to understand the nature and workings of nineteenth-century gender in all its complexity.

[1] In addition to `Climbing plants’, Darwin sent `Dimorphic condition in Primula‘ and probably `Three forms of Lythrum salicaria‘. See Becker’s letter of thanks for more detail.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Charles Darwin, Correspondence, Darwin, Education, Feminism, Gender, gender ideology, Harriet Mill, J S Mill, letters, Lydia Becker, Manchester Ladies' Literary Society, New wave feminism, private, public, Science, Sexual equality, Subjection of Women, Suffrage, women in science, Women's education | Leave a Comment »

In March 1872 Gaston de Saporta, a French paleobotanist, penned a letter to Darwin offering two pieces of evidence in support of Darwin’s theory on the common ancestry of man and ape.

In March 1872 Gaston de Saporta, a French paleobotanist, penned a letter to Darwin offering two pieces of evidence in support of Darwin’s theory on the common ancestry of man and ape.

The first point of similarity between the two species, Saporta argued, was dentition; the arrangement of teeth in the mouth of humans and simians , he said, “seems to denote an exclusive link with the Monkeys of the old continent“. The second similarity was decidedly more risqué, namely “female menstruation and, as a corollary, the odour which makes women attractive to many monkeys“.

Alongside other similarities – including bald foreheads and the direction of hairs on the forearm – analogous dentition in apes and humans was something which Darwin had already discussed at length in Descent of Man, published the previous year. Nowhere in the body of Descent, however, did Darwin mention the menstrual cycle or, more specifically, scent-based sexual attraction between monkeys and humans.

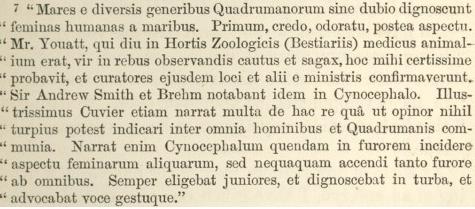

That is not to say, however, that Darwin was ignorant of the issue. Embedded in a footnote and suitably “veiled in Latin”(just as his cautious editor, John Murray, had recommended) Darwin refers to the role of smell – “odoratu” – in the courtship processes of humans and apes alike. By presenting this sort of content in Latin, Darwin was able to protect the sensibilities of his general readership without depriving his learned audience of a piece of evidence which corroborated his theory of the shared heredity of man and ape. [1]

That is not to say, however, that Darwin was ignorant of the issue. Embedded in a footnote and suitably “veiled in Latin”(just as his cautious editor, John Murray, had recommended) Darwin refers to the role of smell – “odoratu” – in the courtship processes of humans and apes alike. By presenting this sort of content in Latin, Darwin was able to protect the sensibilities of his general readership without depriving his learned audience of a piece of evidence which corroborated his theory of the shared heredity of man and ape. [1]

Interestingly, even once shrouded in a decorous cloak of Latin, Darwin remained sketchy on detail: “Males from various species of mammals”, he said, “clearly distinguish anthropomorphous females from male. First, I believe, by smell, then by appearance.” In conceding that the topic in question was “turpius” (i.e. unseemly) in character, one can justifiably conclude that the odaratu to which Darwin referred was similar in kind to that observed and communicated by Saporta.

What was it about this topic which rendered it taboo? Evidence from elsewhere in the correspondence suggests that Darwin felt uncomfortable discussing the topic of menstruation, at least in public. When the medical director of Wakefield Asylum wrote to him to report the case of a woman inmate who believed that she was pregnant until “a distinct return of menstruation”, for example, he replied that while “truly wonderful” the topic could not feature “in any work not strictly medical”. “Perhaps I may manage to give it wrapped up,” he said, “or anyhow allude to it”.

Darwin might also have felt uncomfortable about the potential impropriety of drawing parallels between the courtship processes of man and ape. As Gillian Beer has noted, in the wake of the publication of Descent there existed a certain “sexual distate…for many Victorians in the idea of kinship with other animal species”. [2]

Darwin might also have felt uncomfortable about the potential impropriety of drawing parallels between the courtship processes of man and ape. As Gillian Beer has noted, in the wake of the publication of Descent there existed a certain “sexual distate…for many Victorians in the idea of kinship with other animal species”. [2]

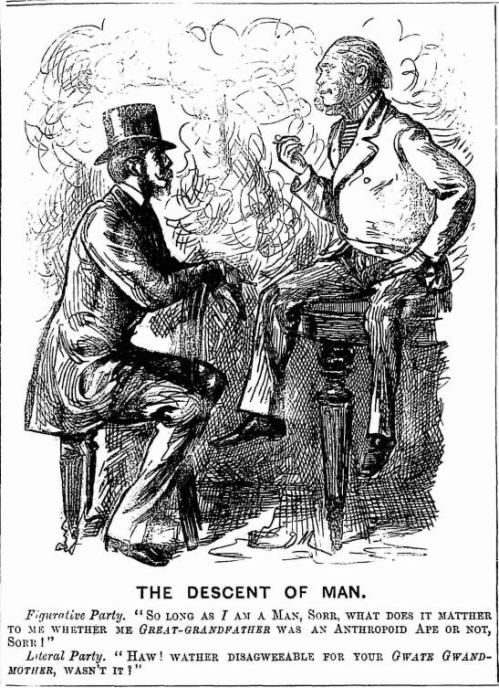

Distaste at the sexual implications of Darwin’s theory of shared heredity was played out at length in the popular press where images such as The Descent of Man and That Troubles Over Our Monkey Again encapsulated Victorian society’s sense of unease with the notion that humans had, at some stage, shared their beds with apes. [3]

Distaste at the sexual implications of Darwin’s theory of shared heredity was played out at length in the popular press where images such as The Descent of Man and That Troubles Over Our Monkey Again encapsulated Victorian society’s sense of unease with the notion that humans had, at some stage, shared their beds with apes. [3]

Gaston de Saporta’s correspondence helps bring to light the strategies which Darwin could (and indeed did) employ in order to pitch his work both as a palatable read for his respectable popular audience and – at the same time – a robust and convincing work of science. It also helps us to better understand hierarchies of impropriety in Victorian Britain. Thus, while Darwin deemed certain risqué topics to be suitable for a learned (if not popular) readership, other subjects – including menstruation – remained taboo in all but the most private of contexts.

[1] For more on this subject see Gowan Dawson, Darwin, Literature and Victorian Respectability, (Cambridge, 2007), p. 37.

[2] Gillian Beer, ‘Forging the Missing Link’ in Open Fields: Science in Cultural Encounter, (Oxford, 1999), pp. 131 – 132.

[3] Gordon Thomson, That Troubles Over Our Monkey Again (Fun 16, 1872) featured Darwin as half-man half-monkey, complete with conspicuously erect tail. George du Maurier, Descent of Man (Punch 64, 1873) complete with lewd reference to a sexual encounter between an ape and the featured character’s ancestor.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged attraction, Charles Darwin, cross-species, Darwin, Descent of Man, Gaston de Saporta, history of science, menstruation, respectability, scent, Women | Leave a Comment »

Charles Darwin was not just a eminent Naturalist – he was also the head of a thriving family economy who drew on the help of his relatives at any (and, it seems, every!) opportunity. His eldest son, William, was regularly tasked with observing plants and animals for him, while Charles’ second son, George, helped him with complex maths problems. Francis, meanwhile, was always on hand to check and correct Darwin’s mediocre Latin.

Charles Darwin was not just a eminent Naturalist – he was also the head of a thriving family economy who drew on the help of his relatives at any (and, it seems, every!) opportunity. His eldest son, William, was regularly tasked with observing plants and animals for him, while Charles’ second son, George, helped him with complex maths problems. Francis, meanwhile, was always on hand to check and correct Darwin’s mediocre Latin.

Darwin’s women relatives weren’t left out; his daughter, Henrietta, acted both as an observer and a trusted editor, while his wife, Emma, would copy out his manuscripts and check his proofs. As Francis Darwin recalled, Emma would read Charles’ work, “chiefly for misprints and to criticise punctuation; & then my father used to dispute with her over commas especially”. [1]

Darwin’s workforce wasn’t limited to his nuclear family; he also drew on the advice of his cousin, on the observational skills of his nieces and, later in life, on the advice of Henrietta’s husband and the observational skills of Francis’ fiancée.

Darwin’s work, then, was the product of a collective familial effort and his private letters suggest that he was extremely grateful for the contribution made by his relatives; “All your remarks, criticisms doubts & corrections are excellent, excellent, excellent”, he told Henrietta in 1867. “My dear Angels!,” he wrote to his nieces in 1862, “I can call you nothing else.—I never dreamed of your taking so much trouble; the enumeration will be invaluable.”

While Darwin clearly valued the work of his relatives regardless of their sex, in the public sphere the case was very different. Thus, while the contributions of Charles’ male relatives were methodically acknowledged in his published works, the input of women was not.

In his 1862 publication The Fertilisation of Orchids, for example, Charles publicly acknowledged the observational contributions made by “my sons” George (p. 16), William (p. 99) and Francis (p. 273). Charles was careful to acknowledge his sons’ work in all of its forms; regular – and notably proud – references were made in Insectivorous Plants, for example, not just to his boys’ skills of observation but also to other sorts of labour, including the illustration of botanical diagrams (p. 3) and mathematical skills (p. 173).

In his 1862 publication The Fertilisation of Orchids, for example, Charles publicly acknowledged the observational contributions made by “my sons” George (p. 16), William (p. 99) and Francis (p. 273). Charles was careful to acknowledge his sons’ work in all of its forms; regular – and notably proud – references were made in Insectivorous Plants, for example, not just to his boys’ skills of observation but also to other sorts of labour, including the illustration of botanical diagrams (p. 3) and mathematical skills (p. 173).

Charles was equally careful to acknowledge the contributions – however fleeting – of other male family members. Richard Litchfield’s contribution to a discussion of music (discussed in this letter), for example, was carefully referenced in Expression (p. 89). Similarly, Hensleigh Wegwood – Darwin’s cousin – was acknowledged for the contribution that he made (discussed here) to a section on language in Descent (p. 56).

Darwin’s published materials give only a partial insight, however, into the workings of the Darwin family economy. Indeed, without Darwin’s letters, a large and significant part of his workforce would remain entirely invisible. The key question, of course, is why did Darwin’s female workforce remain invisible to the public eye?

It wasn’t, it seems, an issue of trust: Evidence shows very clearly that Charles respected the work undertaken by his women relatives. Henrietta’s observations of domestic cats and her (and her female friends’) observations of babies, for example, both featured (albeit anonymously) in Expression of Emotion. [2] Samples and observations provided by Lucy Wedgwood were similarly referenced in Forms of Flowers (p. 70), referred to simply (and anonymously) as having been provided by “a friend in Surrey”.

It wasn’t, it seems, an issue of trust: Evidence shows very clearly that Charles respected the work undertaken by his women relatives. Henrietta’s observations of domestic cats and her (and her female friends’) observations of babies, for example, both featured (albeit anonymously) in Expression of Emotion. [2] Samples and observations provided by Lucy Wedgwood were similarly referenced in Forms of Flowers (p. 70), referred to simply (and anonymously) as having been provided by “a friend in Surrey”.

It seems, then, that Charles’ anxiety lay not with the type or quality of work that his women relatives produced but with the consequences of making that work public. At a time when a middle class woman’s femininity was measured by her modesty and unwavering dedication to the well-being of her home and family, Darwin’s concerns about making the work of his daughter, wife and other female relatives public were, on some level, entirely understandable.

[1] The recollections of Francis Darwin; CUL DAR 112:144.

[2] See, for example, Expression, pp. 126 – 9. See also letter 5332 and 7153 in which Henrietta and Mary Lubbock provide observations which fed into Expression (p. 153). Henrietta’s observations on house cats’ cries from DAR 189:7 are also mentioned on p. 60 of Expression).

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Charles Darwin, Darwin, Descent of Man, Emma Darwin, Emma Wedgwood, Expression of Emotion, family, Fertilisation of Orchids, Forms of Flowers, Gender, Henrietta Darwin, labour, Lucy Wedgwood, private, public, separate spheres, Victorian, Women, work | 3 Comments »

As part of a course on Gender, Sex and Evolution led by Professor Sarah Richardson, students at Harvard University have road-tested our resources and produced a series of projects on the theme of Darwin and Gender.

The students’ brief was 1) to design a set of projects which highlight the value of the Darwin and Gender research initiative and 2) to explore the contribution that our work might make to Gender History and Gender Studies.

Five of the most exciting projects will appear on the Darwin Correspondence Project website in the very near future. For now, take a sneak peek at one student’s inspired, TV-quiz-show-themed video response.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Collaboration, Darwin, Darwin Correspondence Project, evolution, Gender, Harvard, resources, sex, university | Leave a Comment »

One question which arises a lot when sifting through Darwin’s letters is are we prying? Did Darwin and his correspondents consider their letters to be public objects or private exchanges intended only for the eyes of the sender and recipient in question? The answer appears to be both.

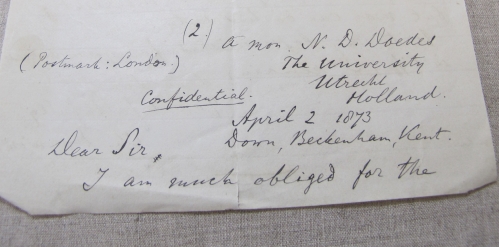

As a rule, Darwin’s correspondents tended to state explicitly when a letter (or a specific section of a letter) was “private” or “confidential” – a custom which suggests that they assumed that their written exchanges were by default public property, or at least potentially so.

As a rule, Darwin’s correspondents tended to state explicitly when a letter (or a specific section of a letter) was “private” or “confidential” – a custom which suggests that they assumed that their written exchanges were by default public property, or at least potentially so.

In Darwin’s case, the practice of flagging-up private content developed out of – perhaps bitter! – experience. As he explained to one of his correspondents in 1871; “I put “private” from habit only as yet partially acquired, from some hasty notes of mine having been printed, which were not in the least degree worth printing.”

Darwin perhaps referred in part here to a frustrating experience he had in 1857 when William Sharpey read content from one of his letters to the Council of the Royal Society. Darwin’s annoyance over this transgression is clear both in a letter he wrote to Hooker on the subject and in an uncharacteristically confrontational reply he wrote to Sharpey.[1]

Even where an explicit request was made for a letter to remain private, however, it was impossible to ensure that it did. As scholars of the epistolary form have shown over and again, despite best intentions letters have a habit of hanging around and ultimately being consumed by a far wider public audience than was perhaps intended. [2]

Even where an explicit request was made for a letter to remain private, however, it was impossible to ensure that it did. As scholars of the epistolary form have shown over and again, despite best intentions letters have a habit of hanging around and ultimately being consumed by a far wider public audience than was perhaps intended. [2]

Interestingly, some of Darwin’s correspondents seem to have been aware of this risk. Thus, when dealing with content that was deemed especially sensitive, some correspondents requested that their letters be burned after reading.

One extremely rare example of a male correspondent who made this request is provided by John William Salter, a Geologist and Paleontologist who wrote to Darwin on new year’s eve, 1866 to ask him for help in supporting his family; “Are you rich enough to aid me at all,” he asked, “—and make me your debtor for any help I can give in looking over the paleozoic part of your reasonings in your great book.” Salter signed off his letter by stating that, “I trust you will burn my letter— I had hoped for so different a career—”. As far as Salter was concerned, then, sensitive content equated to professional failure, unemployment and the inability to act as breadwinner and support his wife and children.

For women the case was very different. Where a middle class man’s public reputation hinged on his professional and financial success, a middle class woman’s reputation was measured by her modesty and chastity.

The vast majority of ‘burn this’ requests in the Darwin archive can be found in the correspondence of Fanny Owen, a woman who Darwin courted as a young man. Tame as the content is, Owen was evidently anxious about the letters she exchanged with Darwin, ending most of her correspondence with statements such as, “Burn this as soon as you have made out the nonsense“, “you must burn this when you get it” and – shortly before Darwin left on the Beagle – “Burn this before you sail for pitys sake“.

Owen’s repeated requests that her letters be destroyed reflect the pressures that she laboured under as a young middle class woman whose volatile reputation depended primarily on her modesty and chastity. These characteristics were key a part of her feminine status and crucial if she was successfully to secure a husband and thus future happiness. As she herself said to Darwin in 1828, “For Heaven’s sake burn this, or if it falls into the hands of any of the young men, what would they think”. [3]

While some of the letters in Darwin’s archive were never meant for public consumption, there is a great amount to be gained from an analysis of “public” and “private” letters alike. A comparative analysis of these different sorts of correspondence helps us to develop a sense of what kinds of information and styles of delivery were deemed appropriate – and indeed inappropriate – for the public sphere. We also get a sense of how public profiles were constructed and, crucially, the means by which they might have been undermined. More fundamentally, an analysis of Darwin’s most confidential letters reminds us of the serendipitous and incomplete nature of his archive. After all, we will never know for sure how many letters managed to remain private nor how many Darwin burned after reading.

[1] In this instance Darwin’s concern was for his professional reputation which was built on well-crafted ideas and considered, balanced prose; “[I] fear I expressed myself dogmatically“, he told Hooker. More generally, the letters/content which Darwin marked as explicitly private or confidential falls neatly into two categories: one which, like the Sharpey case, concerned his professional status and another which concerned religion – a controversial topic which he was always reluctant to discuss publicly.

[2] For an introduction to the historiography of the epistolary form see Rebecca Earle (ed.), Epistolary Selves: Letters and Letter-Writers 1600 – 1945, (Aldershot, 1999).

[3] For more on the gendered workings of the courtship ritual see Laura Gowing, ‘The economy of courtship’, in her Domestic Dangers, (Clarendon, 1996).

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Beagle, burn after reading, censorship, Charles Darwin, chastity, confidential, Darwin, editorial process, epistolary, Fanny Owen, feminine, Gender, gentleman, John William Salter, Joseph Hooker, Laura Gowing, letter writing, letters, masculine, men, modesty, private, public, Rebecca Earle, reputation, Victorian gender, William Sharpey, Women | 3 Comments »

International Women’s Day celebrates the achievements of women, particularly those who have struggled to participate in society on an equal footing with men. Darwin’s correspondence is a rich source of evidence of extraordinary women who did just that; from international travellers and diamond prospectors to naturalists, botanists, entomologists and pioneering members of the suffrage movement.

International Women’s Day celebrates the achievements of women, particularly those who have struggled to participate in society on an equal footing with men. Darwin’s correspondence is a rich source of evidence of extraordinary women who did just that; from international travellers and diamond prospectors to naturalists, botanists, entomologists and pioneering members of the suffrage movement.

Lydia Becker (1827 – 1890), for example, was not just paid secretary of the National Society of Women’s Suffrage, president of the Manchester Ladies’ Literary Society, editor of the Women’s Suffrage Journal and founding member of the Married Women’s Property Commission — she was also a keen botanist, a published science writer and a correspondent of Charles Darwin.

Lydia Becker (1827 – 1890), for example, was not just paid secretary of the National Society of Women’s Suffrage, president of the Manchester Ladies’ Literary Society, editor of the Women’s Suffrage Journal and founding member of the Married Women’s Property Commission — she was also a keen botanist, a published science writer and a correspondent of Charles Darwin.

Antoinette Brown Blackwell (1825 – 1921) was the first woman to be ordained as a minister in the United States, a vociferous social reformer and promoter of women’s rights. She was also a keen philosopher and scientist who, like Becker, published scientific works and corresponded with Charles Darwin.

Antoinette Brown Blackwell (1825 – 1921) was the first woman to be ordained as a minister in the United States, a vociferous social reformer and promoter of women’s rights. She was also a keen philosopher and scientist who, like Becker, published scientific works and corresponded with Charles Darwin.

The achievements of women like Becker and Blackwell should not be underestimated; at a time when science was deemed a gentlemanly pursuit reserved for the so-called “rational sex”, they were part of a select group of women who broke the trammels and defied gender ideology in order to participate in the masculine world of science.[1] In this way Becker and Blackwell’s science embodied their politics; they attempted to eradicate inequality and make a masculine pursuit sexless and universal.

In real terms, however, Becker and Blackwell were far from the equals of Darwin and his male corespondents. Denied access to formal scientific education and refused membership of formal societies, women scientists existed somewhere on the periphery of the world of institutional science. While Becker and Blackwell were able to access the world of science through the private and appropriately feminine channel of letter-writing, their involvement in the public world of science was severely limited by dominant gender ideology which celebrated women as moral and feeling but ultimately irrational and thus destined by their nature to be domestic, nurturing creatures.

The notion of the private, domestic middle class woman was so pervasive in nineteenth-century Britain that scientific women often felt compelled to publish their works anonymously; Becker’s 1864 publication Botany for Novices , for example, was published under her initials, a strategy which – alongside her detached narrative and deliberate use of gentlemanly discourse – left her work free from any suggestion that it might have been produced by a woman.

Darwin’s letters suggest that while he was open to the concept of women being involved in the world of science (he relied heavily on women observers, for example), his default position was that science and scientific correspondence was the preserve of men. Thus, when Antoinette Brown Blackwell sent a copy of her Studies in General Science to Darwin in 1869, he assumed from its content and subject matter that its author – “A. B. Blackwell” – was male; “Dear Sir,” Darwin wrote in reply, “I am much obliged to you for your kindness in sending me your “Studies in General Science”, over which, as I observe in the Preface, you have spent so much time.”

Darwin’s letters suggest that while he was open to the concept of women being involved in the world of science (he relied heavily on women observers, for example), his default position was that science and scientific correspondence was the preserve of men. Thus, when Antoinette Brown Blackwell sent a copy of her Studies in General Science to Darwin in 1869, he assumed from its content and subject matter that its author – “A. B. Blackwell” – was male; “Dear Sir,” Darwin wrote in reply, “I am much obliged to you for your kindness in sending me your “Studies in General Science”, over which, as I observe in the Preface, you have spent so much time.”

International Women’s Day offers us an important opportunity to celebrate the achievements of great women past and present. Celebrating the achievements of women should not, however, make us blind to the cultural barriers which stood and continue to stand in the way of sexual equality. Today should not just be about celebrating the achievements of great women but also about appreciating the ongoing nature of their struggle. In a world where girls continue to be deterred from studying science at school and where women still find it difficult to enter the scientific professions, it is clear that while some women’s battles have been won, others – including that of Becker and Blackwell – are ongoing.

[1] For a discussion of the so-called “masculinisation” of science – particularly botany – in the nineteenth century see A. Schteir, Cultivating Women, Cultivating Science, (John Hopkins University Press, 1999).

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Antoinette Brown Blackwell, Darwin, Education, equality, Gender, inequality, international women's day, Lydia Becker, Manchester Ladies' Literary Society, Married Women's Property Commission, National Society of Women's Suffrage, Science, Suffrage, Women, women in science, Women's Suffrage Journal | 2 Comments »

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged "word cloud", Darwin, Gender, Wordle | Leave a Comment »

This month is LGBT History Month, an annual event which celebrates the lives of the LGBT community both past and present. The event helps draw attention to the ongoing work of organisations like Schools Out, which encourage teachers to give lessons on ‘significant’ gay people like Alan Turing, the forefather of modern computing whose work as a Cryptanalyst helped to defeat Nazi Germany. Alternatively, teachers might opt to take Science lessons based on research which shows that homosexual behaviour typically occurs in hundreds of species of animals. [1]

This month is LGBT History Month, an annual event which celebrates the lives of the LGBT community both past and present. The event helps draw attention to the ongoing work of organisations like Schools Out, which encourage teachers to give lessons on ‘significant’ gay people like Alan Turing, the forefather of modern computing whose work as a Cryptanalyst helped to defeat Nazi Germany. Alternatively, teachers might opt to take Science lessons based on research which shows that homosexual behaviour typically occurs in hundreds of species of animals. [1]

Any Science teachers who try to draw on Darwin’s work in this context will be rather disappointed with what they find. Despite dedicating his life to the observation of the natural world, no reports of homosexual behaviour appear ever to have been made by Darwin.[2] This is surprising given that recent academic research shows overwhelmingly that “nearly all species” of animals exhibit some degree of homosexual behaviour both in the wild and in captivity.

Expert observations of Rhesus monkeys’ behaviour, for example – behaviour which Darwin studied very closely – has shown conclusively that both male and female members of the species demonstrate homosexual as well as heterosexual behaviour over the course of their lives. Thus, according to Professor Paul Vasey, same-sex Rhesus monkeys are typically “affectionate to each other, touching, holding and embracing” one another.[3]

Expert observations of Rhesus monkeys’ behaviour, for example – behaviour which Darwin studied very closely – has shown conclusively that both male and female members of the species demonstrate homosexual as well as heterosexual behaviour over the course of their lives. Thus, according to Professor Paul Vasey, same-sex Rhesus monkeys are typically “affectionate to each other, touching, holding and embracing” one another.[3]

Darwin’s observations of Rhesus monkey behaviour were decidedly more hetero-normative, focussing exclusively on interactions between the sexes at the expense of interactions within single-sex pairings. As an animal of “the order to which man belongs“, Rhesus monkey courtship behaviour appeared to Darwin as identical to the human equivalent – a heterosexual, male-driven process in which “ornamental” females were selected according to their perceived physical attractiveness.

So why did Darwin and his contemporaries fail to observe the homosexual behaviour which naturally occurs in species like the Rhesus monkey? Part of the answer undoubtedly lies in Victorian Britain’s narrow definition of sexuality. While during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries sexual acts between people of the same sex were deemed “part and parcel of ‘normal’ sexual behaviour”, over the course of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries “natural” sexuality became more narrowly defined as productive, marital and thus heterosexual.[4]

As a man who dedicated his life to analysing the selective forces which influenced the evolutionary process – from the weather, to geography, to physical strength and aesthetic adornments – one would expect Darwin to have taken a keen interest in the potentially critical evolutionary consequences of same-sex behaviour in animals and humans alike. In neither his public work nor private letters, however, did he describe sexuality as anything other than a heterosexual/reproductive phenomenon; “Sexuality”, he told Charles Lyell in 1861, should be defined as the uniting of “two elements” which “go to form the new being“.

As a man who dedicated his life to analysing the selective forces which influenced the evolutionary process – from the weather, to geography, to physical strength and aesthetic adornments – one would expect Darwin to have taken a keen interest in the potentially critical evolutionary consequences of same-sex behaviour in animals and humans alike. In neither his public work nor private letters, however, did he describe sexuality as anything other than a heterosexual/reproductive phenomenon; “Sexuality”, he told Charles Lyell in 1861, should be defined as the uniting of “two elements” which “go to form the new being“.

In a world where homosexual behaviour was increasingly labelled “unnatural”, it might have been the case that Darwin simply did not see homosexual behaviour in the natural world – that he was somehow culturally blinded to its existence in nature. Alternatively, it might have been the case that as an aspiring respectable man of science whose work was considered by many to tread a fine line between “real” scientific endeavour and “indecent aestheticism”, Darwin lacked the freedom to observe, discuss and thus “naturalise” types of behaviour which had the potential to offend and alienate his middle-class audience.[5]

While Darwin’s work does little to help teachers convey the complexity of human sexuality to their students, it nonetheless provides an extremely rich insight into the relationship between science and culture. Contrary to what we tend to be taught at school, it is impossible for even the most dedicated and “detached” of scientists to offer insights that are entirely objective and wholly a-political. In looking at Darwin’s work both as a piece of science and as a product of culture, students can learn valuable lessons about the subjectivity of what we “know” and about the ways and means by which heterosexuality has been constructed as the norm from which other sorts of sexuality diverge.

[1] For discussions of homosexual behaviour in the animal kingdom see Volker Sommer & Paul L. Vasey, Homosexual Behaviour in Animals, An Evolutionary Perspective, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), Bruce Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, (London, 1999) and Frans De Waal & Frans Lanting, Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape, (California, 1998).

[2] There is a single reference to homosexual behaviour in animals in a rather distressing letter written to Darwin by Robert Swinhoe in 1865. Interestingly, in the letter Swinhoe interprets a violent dog fight as motivated by an innate homophobic instinct. There is no reply from Darwin that we know of, but it is significant that the issue of homosexuality does not feature in any of his discussions of dog behaviour in Variation, Descent or Expression.

[3] Sommer & Vasey, Homosexual Behaviour in Animals, (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

[4] See T. Hitchcock, ‘The Development of Sexuality’, English Sexualities 1700 – 1800, (London, 1997), p. 65. Generally speaking, while in the earlier period masculinity was measured by the quantity of sex a man had, by the early nineteenth century it was increasingly measured by its (heterosexual) quality.

[5] For a discussion of the cultural pressures under which Darwin laboured see G. Dawson, Darwin, Literature and Victorian Respectability,(Cambridge, 2007), introduction.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Alan Turing, Animal homosexuality, Bruce Bagemihl, Darwin, Frans de Waal, Frans Lanting, History of sexuality, LGBT History Month, Paul Vasey, Rhesus monkey, Schools Out, Sexuality, Victorian sexuality, Volker Sommer | 3 Comments »

On September 4th 1850, Charles Darwin penned a letter to his cousin and friend William Darwin Fox in which he reported that he and Emma were “at present very full of the subject of schools”. As a middle class family, the Darwins had a number of options to choose from: they could follow in Fox’s footsteps and home school their sons, they could send their boys to a grammar school, or they could opt to educate them at public school where they would receive a classical education centered around the study of Latin and Greek.

On September 4th 1850, Charles Darwin penned a letter to his cousin and friend William Darwin Fox in which he reported that he and Emma were “at present very full of the subject of schools”. As a middle class family, the Darwins had a number of options to choose from: they could follow in Fox’s footsteps and home school their sons, they could send their boys to a grammar school, or they could opt to educate them at public school where they would receive a classical education centered around the study of Latin and Greek.

Charles clearly had considerable reservations about the latter option; “I cannot endure to think of sending my Boys to waste 7 or 8 years in making miserable Latin verses,” he told told Fox. In a later, more candid exchange Darwin declared that, “No one can more truly despise the old stereotyped stupid classical education than I do.”

Why did Darwin object so vehemently to classical education? According to Charles, a classical education had a “contracting effect” on young boys’ minds; it entailed “no exercise of the observing or reasoning faculties,—no general knowledge acquired.” It was, he said, “a wretched system”. Darwin’s preference seems to have been for the more diverse and skills-focussed education offered by grammar schools; “we have heard some good of Bruce Castle School, near Tottenham“, he told Fox in 1850, “which is partly [based] on the Fellenberg System”. [1]

Despite his reservations, however, in 1852 Charles reluctantly reported that his son, William, had embarked on a classical education; “I have not had courage,” Darwin confessed to Fox, “to break through the trammels. After many doubts we have just sent our eldest Boy to Rugby”.

Despite his reservations, however, in 1852 Charles reluctantly reported that his son, William, had embarked on a classical education; “I have not had courage,” Darwin confessed to Fox, “to break through the trammels. After many doubts we have just sent our eldest Boy to Rugby”.

Why such an orthodox move from a man considered to be something of a maverick? The answer most likely lies in prevailing middle class gender ideology. A classical education may have lacked diversity and the opportunity for creativity, but it provided access to an exclusive middle class masculine world. As Anthony Fletcher has shown, Latin was “the male elite’s secret language, a language all of its own, a language that that could be displayed as a mark of learning, superiority, of class and gender difference.” [2]

Classical education held a practical appeal also; monotonous, solid study in subjects with little intrinsic interest for its students was well-designed to check youthful high spirits and transform boys into studious, dedicated and all-round decent middle class men. As Darwin commented to Fox, “a Boy who has learnt to stick at Latin & conquer its difficulties, ought to be able to stick at any labour.”

Classical education held a practical appeal also; monotonous, solid study in subjects with little intrinsic interest for its students was well-designed to check youthful high spirits and transform boys into studious, dedicated and all-round decent middle class men. As Darwin commented to Fox, “a Boy who has learnt to stick at Latin & conquer its difficulties, ought to be able to stick at any labour.”

Charles might have considered William’s schooling “stupid” and “wretched”, but as a middle class father concerned for his son’s professional future and progression into manhood, a classical education ultimately proved too valuable an opportunity for him to miss.

[1] The Hill School at Bruce Castle was a relatively radical institution founded by Rowland Hill, a close friend of Thomas Paine, Richard Price and Joseph Priestly. The Fellenberg System prioritised learning through experience, primarily through the study and practice of agriculture.

[2] Anthony Fletcher, Gender Sex and Subordination, (London, 1995), p. 302.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Charles Darwin, classical education, Darwin, Education, family, Gender, Masculinity, victorian britain, william darwin fox | Leave a Comment »